Ownership

The Dilemma of the Mug

What are our belongings and what does it mean to own them? From a superficial perspective, belongings are things or objects someone has found, made, bought, or been given. They are connected to us and we have legal rights to possess and do almost whatever we please with them. Yet, we often seem to forget that our lives are finite. And so, with our deaths and endings, comes the ending of our personal belongings. Things may have been owned by someone before us, and may be owned by something after us. In other words, to state that you own something needs to be clarified. We own things during our lifetime. Not before and not after. Therefore, in order to take account of longer arcs of time, it might be more reasonable to talk about things as owning themselves, or one another. Humans might be just one of the temporary holders or caretakers.

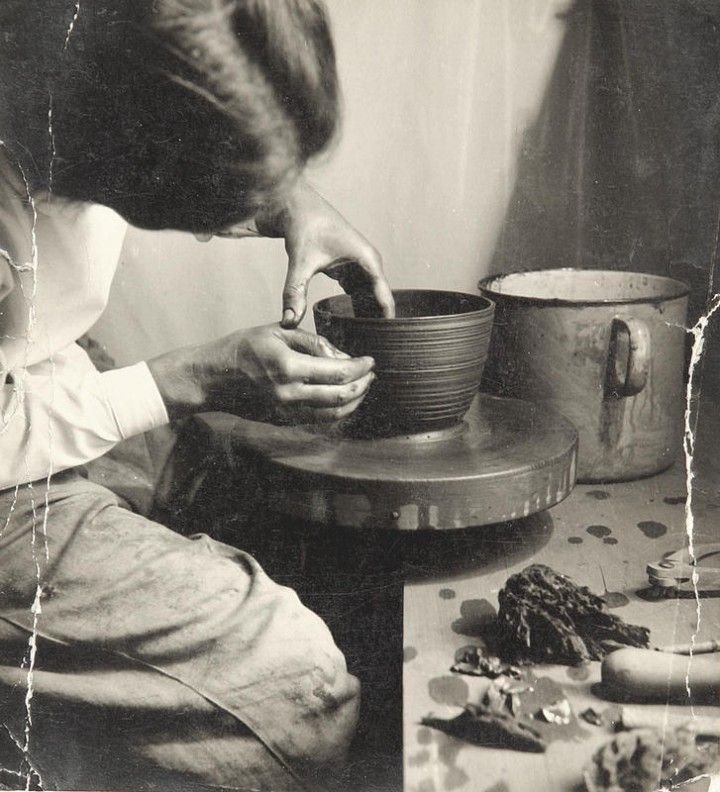

We could take a coffee mug as an example. This specific mug was bought with money by someone who sees themselves as its owner. Or perhaps they gave it away to a second person who in their turn sees themselves as the owner. In any case, the mug is seen as a belonging to a person. No one can come along and walk away with the mug without being labelled a thief. Yet once, the mug was made in clay – a material coming from Earth. Someone dug up a piece of muddy soil and claimed it theirs. They later sold it to a ceramicist who by handing over money claimed the clay as now being theirs. The ceramicist transformed the clay into a mug and the material was sold once again.

Products, objects and materials are being transformed and moved around in our systems. We can call it capitalism. We can call it trade. We can call it economic welfare. But in the end, all of these things produced by humans are made from materials coming from Earth.

So who owns Earth? Most would argue no particular humans own the deeper inner parts of our shared planet. But when we reach the surface, the crust, things become enormously more complex. Heavily impacted by colonialism, war and dreadful abuse of power, surface area and land is owned by humans. And some humans only. To backtrack and fully understand how specific stretches of land sit in the hands of few, is an almost impossible task. But no one can deny that land has been brutally taken, stolen, bought, sold, given away and handed around over centuries. Just as land connects us all, so do these awful stories.

If we look at the mug in relation to land ownership, it becomes clear that this is indeed a complex dilemma. A thing or material that no one owned, was pulled into the matrix of ownership and looked upon as private capital. It is not far-fetched to think of this in moral terms; to consider why it is or is not harmful, or greedy.

And to push our thinking even further. What about our own bodies? Our flesh is made up of materials from Earth, but that is a notion we seem to rather have forgotten. Our mothers generously gave away from their own bodies to create the very first parts that would become us. Through food, minerals, vitamins and water, we developed and grew into the constitutions that we are. All of my body is made from Earth. And all of my body will go back to Earth whatever way I may be handled after my death. My body will become soil. And, to follow the earlier logic, I might become a mug.

There is one “belonging” that entirely resists ownership, which we might call the soul. No one can rightly buy anyone else’s soul, because no one has authority (or possibility) to sell it, even their own. If a mug may be partly owned, a soul may not be owned at all.

If we start to understand belongings along such a spectrum, we might be able to look at our usage of finite materials in different ways. If we start to see that private capital and ownership is actually more stolen than we think it is, it might help us become more generous. If we start to express and discuss belongings and ownerships in an honest way, we might be able to shift sturdy beliefs that hold our systems back and start new dialogues and transformative governance built on trust, love and generosity.